Malaparte had not built his house with much help from architects or engineers, but instead, a local stonemason – Adlfo Amitrano. He described Amitrano as “a simple master builder, the best, the most honest, the most intelligent, the most upright that I have ever known”. The winter prior to construction, Malaparte and Amitrano would spend large amount of time on Punta Massullo just feeling the rock. They would lower themselves along a hanging spur of rock and let the wind sweep around them as they absorbed the environment. Malaparte would also speak of his ideas and visions of his house, which Amitrano would either approve or reject.

|

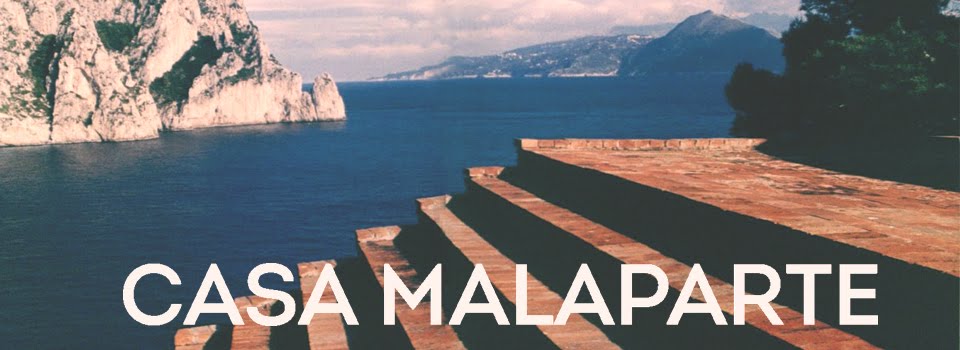

| View from Punta Massullo (source : Visual Photos ) |

When the

construction of Casa Malaparte began, groups of mason arrived on site and

started building from the farthest side of the peninsula. Slowly, the house

began to emerge from the rock. The house was primarily constructed out of stone

and cement, while red bricks were used on the trapezoidal staircase and window and

door openings were constructed with wooden frames. Malaparte wanted his house

to be simple and pure. He refused to follow the style of Capri and to

incorporate elements such as small Romanesque columns, arches, narrow exterior

stair ways, or ogival windows. He thought that the hybrids between the moorish,

romanesque, gothic, and secessionist styles, which the Germans had brought to

Capri around 30 – 50 years before, would contaminate the house.

While Malaparte was absent from Capri during the spring of 1941, his devoted housekeeper, Maria Montico, stayed in Capri to supervise the finishing work and organize the house. During this period, Malaparte grew impatient for the house to be completed. He wrote in a letter to Montico, asking her to urge Amitrano to finish the jobs, and repeat to him that he would not receive a single penny if he does not finish them. Malaparte also sent letters to Amitrano, giving instructions on which part of the house he wanted to be built within a certain period of time. During that period, the floors were to be completed and the tiles were also laid in the downstairs bathroom and the boiler room. Malaparte instructed the fissures to be plastered so that they can be painted. The door from the pantry to the kitchen, that from the pantry to the maid’s room, and that leading from the maid’s room to the service staircase would be built out of wood and mounted. Malaparte also ordered arenaria flagstones from Castellammare di Stabia, which were to be laid for the floor halls.

Malaparte had hired Adolfo Amitrano’s brother, Giovanni Amitrano, a carpenter, to build the desk, the bookshelves, and the staircase specifically out of seasoned chestnut. In addition to that, Malaparte also specifically ordered several other furniture decors such as the rugs from Fede Cheti and hand woven linen sheets. He even gave precise instructions on the finishing of the details. He ordered the masonry stove to be surfaced with small white tiles instead of blue tiles, emphasizing on “small, not big”. He demanded the curtains to be secured with two small, chrome, L-shaped hooks, au lieu de thumbtacks.

By autumn 1941, the work on the interior of the house was near completion. Because the house was built form local stone, which has been exposed to sea water, brine marks appeared over numerous walls in the house. Ciro Amitrano, son of Adolfo Amitrano, came to Capri and restored the walls in the study, the bedroom, the hall, the pantry, the kitchen, the custodian’s room, and the laundry room. He chiselled off the salt and plastered the walls with water and cement and used an anti-humidity compound for water repellent. He then whitewashed the walls according to Malaparte’s likings.

|

In March 1943,

Malaparte met Carlo A. Talamona and hired him to install tufa braids around all

the opening on the southwestern side of the house as a “strong” decorative

motif. He wrote in his letter to Talamona, “The house must have a hard

character, like a prison, almost, like a fortress, as I have written in the

preface to the second edition of my Fughe in prigione, just published by Vallecchi”. However, Talamona objected the idea in

both practical and aesthetic sense. The construction was highly difficult, as

the black tufa must be cut square, the stone of the architrave must be chiseled. The tufa cannot be cut into sections longer than one meter and the

window panes had to be protected with a wooden board, but cutting the stones

behind would also upset the internal insets and the wooden frame. He also

pointed out the impracticality of the use of the porous material in the humid

climate. Aside from that, Talamona thought that the tufa braids would add to

the chaotic disorder of the façade, which would contribute to the disharmony of

the house. Malaparte agreed and altered his design. He

omitted the tufa braids and installed long-planned iron grilles to mend the

irregularity of the façade. The iron grilles over the window made them resemble jail cells.

|

| A Barred Window (Source: Andrea Jemolo ) |

Because Malaparte was constantly away from Capri, he continued to leave lists of detailed reminders and instructions for Montico regarding the maintenance and finishing touches of his house.

After Malaparte’s death in 1957, the house was abandoned and left to decay and vandalism. Serious restoration of the house began around 1988 under the auspices of the Casa Malaparte Foundation. Due to the inaccessibility of the location, helicopters were eventually used to deliver construction materials such as cement and plaster onto the site for restoration.

|

| (Source: House Like Me, pg. 186 ~ 187) |

Source: Marida Talmonda Casa Malaparte

This is a great inspiring article. I am pretty much pleased with your good work. You put really very helpful information. Keep it up. Keep blogging. Looking to reading your next post.

ReplyDeleteold chicago brick pavers

Thanks, that was a really cool read! vibro stone columns

ReplyDelete